In 2010 I was part of a pilot study of a technology called “UbiSketch” created by computer scientists at UC San Diego. UbiSketch involved making hand-drawn images on special paper that was covered with a fine printed dot pattern. The pen I used had a regular ballpoint nib, but unlike regular pens it also had a tiny camera attached that read the location of the marks I made in relation to the dot pattern printed on the paper. The pen/camera was able to instantaneously read and send digital versions of my drawings to a smartphone, where I then uploaded them to a Facebook folder called “UbiSketchBook.”

There were various bugs and technical problems with the setup, such as the whole thing crashing and losing the digital version of a drawing when I used a lot of detail or worked longer than 15 minutes. The technical limitations dovetailed fortuitously with the constraints of my life at the time, as my younger son had just been born and I was severely sleep deprived and had almost no time for art making or anything else that didn’t involve my son. For one month that summer my art practice consisted of briefly escaping to a nearby café every few days and making a fifteen-minute drawing with the UbiSketch technology and immediately uploading the results to Facebook before it crashed. Then I would stumble back home to the land of diaper changes and baby rocking/burping/feeding/etc.

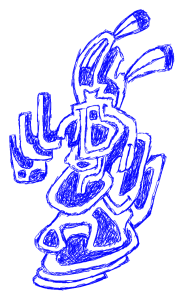

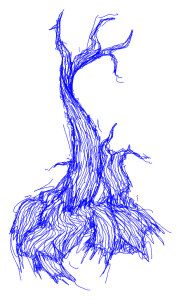

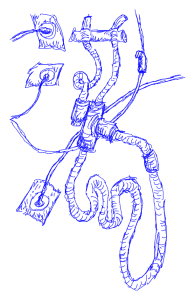

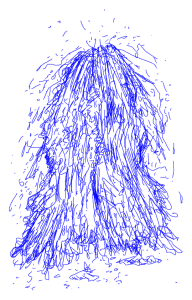

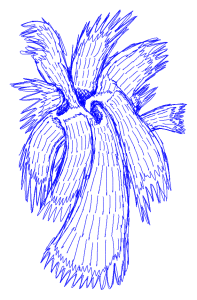

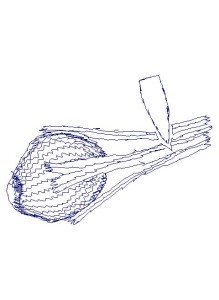

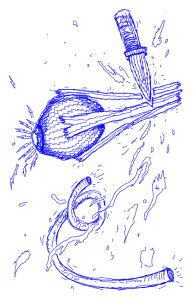

One interesting aspect of the UbiSketch technology was the ability to “save” multiple digital images while the drawing was still in progress. Below is an example of a progression of the drawing called “UbiSketch11-Strabismus Massacre Feared Dead!” using multiple saves:

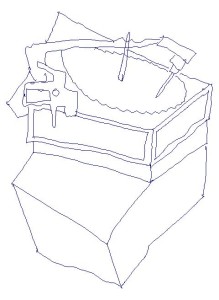

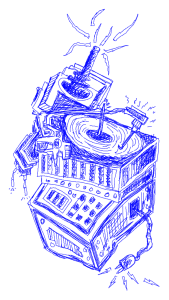

Another example of a progression of multiple saves of the drawing “UbiSketch21-Old School Entertainment System”:

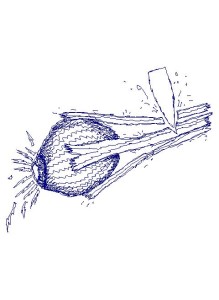

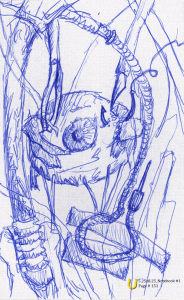

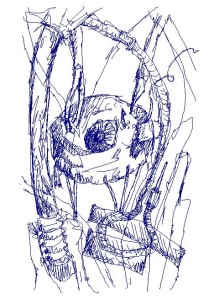

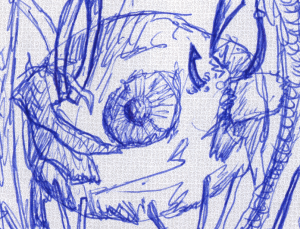

You can compare the differences between a scan of one of the actual pen-on-paper drawings (below, left) to the digital image that was captured via the camera (below, right). Click on scanned drawings for larger, more detailed versions.

This is a detail image of the scanned pen-on-paper version, where you can see the printed dot pattern that the camera reads to make the digital image:

This was a totally different process than simply taking a regular pen-on-paper drawing and scanning and manipulating it on a computer to create a digital image. What was really intriguing for me was to see what the pen/camera technology would capture of the actual moment of real-time creation of these drawings, and how the digital images created during the act of drawing differed from the real drawings on paper. What would the technology capture, what would it miss, and what would it change? For me, this is similar to the process of printmaking, where you begin with an image on a plate and it goes through this almost alchemical process of transformation through the press. The artist has to balance on the edge between being very methodical and precise while at the same time remaining flexible and open to serendipity and the elements that are beyond their control.

Below are more scanned pen-on-paper images next to their pen/camera digital versions. The real pen-on-paper drawings have warmth, depth, variation in line and color, and complexity. The photo/pen digital versions are slick, flat, clean, cold and simplified. It’s kind of like comparing most anything that is analog, or hand/mechanically made, to a digital version: What is gained and what is lost?